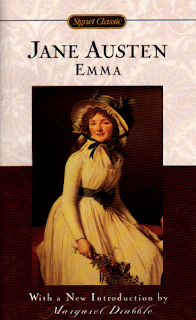

Artifact: Emma, by Jane Austen. Published in 1815.

Artifact background: Emma takes place at a time when true power was inherent in land ownership. The great families are those that own their estates, and the older they are, the longer they have held their land, the more powerful they become. Emma belongs to one such privileged family, the Woodhouse clan of Hartfield estate. George Knightley, one of the few characters superior to Emma, also owns his own land, Donwell Abbey. A new class is being formed by the merchants; wealth is the other key factor in being a great family, although money earned through trade does not have the same prestige as wealth collected from tenants (lords of the land, paid rent by the people working the land). Social structure is everything: you are born to a certain level and society itself tries to keep you there, neither letting you rise nor fall. People are not allowed to venture above their own level; if they try, they are met with scorn and condescension.

I am interested in Emma because Jane Austen wrote it as a satire; she specifically meant for there to be hidden commentary, and I enjoyed searching it out. I love to analyze things, and there’s a wealth of analysis to be found in this book; in essence, I am analyzing Austen’s analysis of her society. What makes it even better is that she is making fun of the flaws in society.

The significance I find in analyzing Emma is to discover just what exactly society was like in 1815. One point I find particularly interesting is discerning how much of the book is satire and how much was, at the time, acceptable social norms to Austen.

I will use ideological criticism to analyze Emma because I find that method to be the most comprehensive when breaking down a novel of Emma’s depth. There’s a lot to be found between the lines, and I want to know just what exactly Austen is saying.